Chapter 29: The Trial

Performer: Librivox - Bridget Gaige

The "prosecuting attorney" (for so the State's attorney is called in Indiana) had been sent for the night before. Ralph refused all legal help. It was not wise to reject counsel, but all his blood was up, and he declared that he would not be cleared by legal quibbles. If his innocence were not made evident to everybody, he would rather not be acquitted on a preliminary examination. He would go over to the circuit court and have the matter sifted to the bottom. But he would have been pleased had his uncle offered his counsel, though he would have declined it. He would have felt better to have had a letter from home somewhat different from the one he received from his Aunt Matilda by the hand of the prosecuting attorney. It was not very encouraging or very sympathetic, though it was very characteristic.

"Dear Ralph:

"This is what I have always been afraid of. I warned you faithfully the last time I saw you. My skirts are clear of your blood, I cannot consent for your uncle to appear as your counsel or to go your bail. You know how much it would injure him in the county, and he has no right to suffer for your evil acts. O my dear nephew! for the sake of your poor, dead mother — "

We never shall know what the rest of that letter was. Whenever Aunt Matilda got to Ralph's poor, dead mother in her conversation Ralph ran out of the house. And now that his poor, dead mother was again made to do service in his aunt's pious rhetoric, he landed the letter on the hot coals before him, and watched it vanish into smoke with a grim satisfaction.

Ralph was a little afraid of a mob. But Clifty was better than Flat Creek, and Squire Hawkins, with all his faults, loved justice, and had a profound respect for the majesty of the law, and a profound respect for his own majesty when sitting as a court representing the law. Whatever maneuvers he might resort to in business affairs in order to avoid a conflict with his lawless neighbors, he was courageous and inflexible on the bench. The Squire was the better part of him. With the co-operation of the constable, he had organized a posse of men who could be depended on to enforce the law against a mob.

By the time the trial opened in the large schoolhouse in Clifty at eleven o'clock, all the surrounding country had emptied its population into Clifty, and all Flat Creek was on hand ready to testify to something. Those who knew the least appeared to know the most, and were prodigal of their significant winks and nods. Mrs. Means had always suspected him. She seed some mighty suspicious things about him from the word go. She'd allers had her doubts whether he was jist the thing, and ef her ole man had axed her, liker-n not he never'd a been hired. She'd seed things with her own livin' eyes that beat all she ever seed in all her born days. And Pete Jones said he'd allers knowed ther warn't no good in sech a feller. Couldn't stay abed when he got there. And Granny Sanders said, Law's sakes! nobody'd ever a found him out ef it hadn't been fer her. Didn't she go all over the neighborhood a-warnin' people? Fer her part, she seed straight through that piece of goods. He was fond of the gals, too! Nothing was so great a crime in her eyes as to be fond of the gals.

The constable paid unwitting tribute to William the Conquerer by crying Squire Hawkins' court open with an Oyez! or, as he said, "O yes!" and the Squire asked Squire Underwood, who came in at that minute, to sit with him. From the start, it was evident to Ralph that the prosecuting attorney had been thoroughly posted by Small, though, looking at that worthy's face, one would have thought him the most disinterested and philosophical spectator in the courtroom.

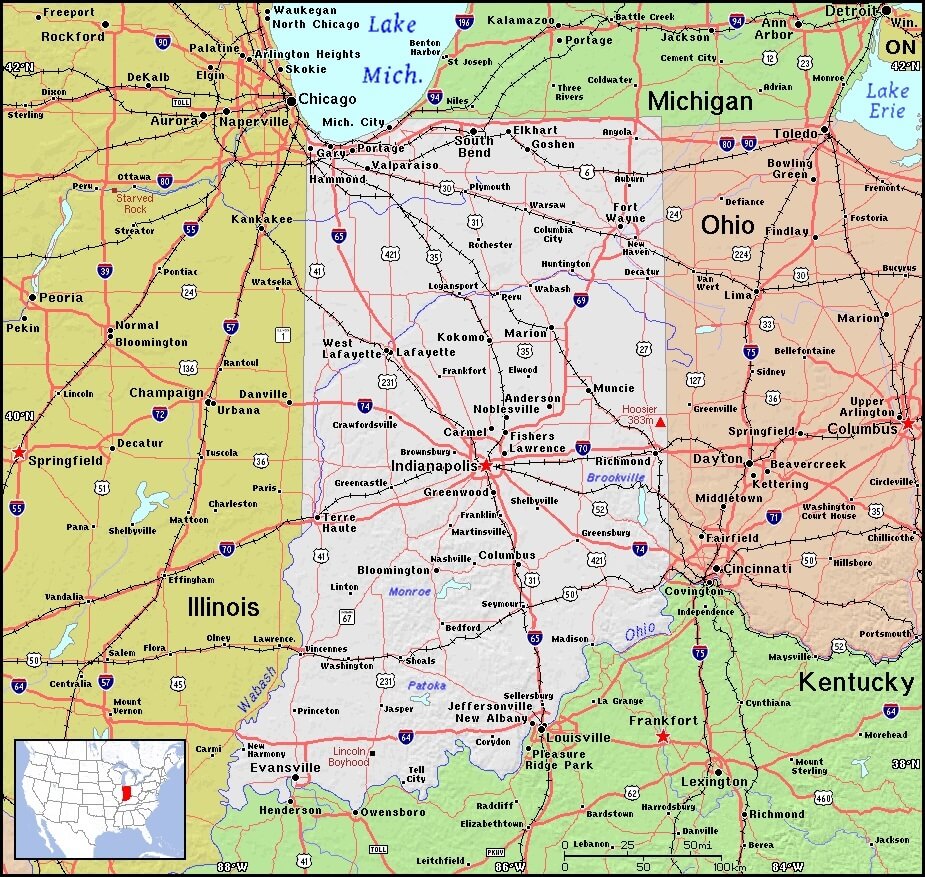

Bronson, the prosecutor, was a young man, and this was his first case since his election. He was very ambitious to distinguish himself, very anxious to have Flat Creek influence on his side in politics; and, consequently, he was very determined to send Ralph Hartsook to State prison, justly or unjustly, by fair means or foul. To his professional eyes this was not a question of right and wrong, not a question of life or death to such a man as Ralph. It was George H. Bronson's opportunity to distinguish himself. And so, with many knowing and confident nods and hints, and with much deference to the two squires, he opened the case, affecting great indignation at Ralph's wickedness, and uttering Delphic hints about striped pants and shaven head, and the grating of prison-doors at Jeffersonville.

"And, now, if the court please, I am about to call a witness whose testimony is very important indeed. Mrs. Sarah Jane Means will please step forward and be sworn."

This Mrs. Means did with alacrity. She had met the prosecutor, and impressed him with her dark hints. She was sworn.

"Now, Mrs. Means, have the goodness to tell us what you know of the robbery at the house of Peter Schroeder, and the part defendant had in it."

"Well, you see, I allers suspected that air young man — "

Here Squire Underwood stopped her, and told her that she must not tell her suspicions, but facts.

"Well, it's facts I am a-going to tell," she sniffed indignantly. "It's facts that I mean to tell." Here her voice rose to a keen pitch, and she began to abuse the defendant. Again and again the court insisted that she must tell what there was suspicious about the schoolmaster. At last she got it out.

"Well, fer one thing, what kind of gals did he go with? Hey? Why, with my bound gal, Hanner, a-loafin' along through the blue-grass paster at ten o'clock, and keepin' that gal that's got no protector but me out that a-way, and destroyin' her character by his company, that a'n't fit fer nobody."

Here Bronson saw that he had caught a tartar. He said he had no more questions to ask of Mrs. Means, and that, unless the defendant wished to cross-question her, she could stand aside. Ralph said he would like to ask her one question.

"Did I ever go with your daughter Miranda?"

"No, you didn't," answered the witness, with a tone and a toss of the head that let the cat out, and set the courtroom in a giggle. Bronson saw that he was gaining nothing, and now resolved to follow the line which Small had indicated.

Pete Jones was called, and swore point-blank that he heard Ralph go out of the house soon after he went to bed, and that he heard him return at two in the morning. This testimony was given without hesitation, and made a great impression against Ralph in the minds of the justices. Mrs. Jones, a poor, brow-beaten woman, came on the stand in a frightened way, and swore to the same lies as her husband. Ralph cross-questioned her, but her part had been well learned.

There, seemed now little hope for Ralph. But just at this moment who should stride into the schoolhouse but Pearson, the one-legged old soldier basket-maker? He had crept home the night before, "to see ef the ole woman didn't want somethin'," and hearing of Ralph's arrest, he concluded that the time for him to make "a forrard movement" had come, and so he determined to face the foe.

"Looky here, Squar," he said, wiping the perspiration from his brow, "looky here. I jes want to say that I kin tell as much about this case as anybody."

"Let us hear it, then," said Bronson, who thought he would nail Ralph now for certain.

So, with many allusions to the time he fit at Lundy's Lane, and some indignant remarks about the pack of thieves that driv him off, and a passing tribute to Miss Martha Hawkins, and sundry other digressions, in which he had to be checked, the old man told how he'd drunk whisky at Welch's store that night, and how Welch's whisky was all-fired mean, and how it allers went straight to his head, and how he had got a leetle too much, and how he had felt kyinder gin aout by the time he got to the blacksmith's shop, and how he had laid down to rest, and how as he s'posed the boys had crated him, and how he thought it war all-fired mean to crate a old soldier what fit the Britishers, and lost his leg by one of the blamed critters a-punchin' his bagonet through it; and how when he woke up it was all-fired cold, and how he rolled off the crate and went on towurds home, and how when he got up to the top of Means's hill he met Pete Jones and Bill Jones, and a slim sort of a young man, a-ridin'; and how he know'd the Joneses by ther hosses, and some more things of that kyind about 'em; but he didn't know the slim young man, tho' he tho't he might tell him ef he seed him agin kase he was dressed up so slick and town-like. But blamed ef he didn't think it hard that a passel o thieves sech as the Joneses should try to put ther mean things on to a man like the master, that was so kyind to him and to Shocky, tho', fer that matter, blamed ef he didn't think we was all selfish, akordin' to his tell. Had seed somebody that night a-crossin' over the blue-grass paster. Didn't know who in thunder 'twas, but it was somebody a-makin' straight fer Pete Jones's. Hadn't seed nobody else, 'ceptin' Dr. Small, a short ways behind the Joneses.

Hannah was now brought on the stand. She was greatly agitated, and answered with much reluctance. Lived at Mr. Means's. Was eighteen years of age in October. Had been bound to Mrs. Means three years ago. Had walked home with Mr. Hartsook that evening, and, happening to look out of the window toward morning, she saw someone cross the pasture. Did not know who it was. Thought it was Mr. Hartsook. Here Mr. Bronson (evidently prompted by a suggestion that came from what Small had overheard when he listened in the barn) asked her if Mr. Hartsook had ever said anything to her about the matter afterward. After some hesitation, Hannah said that he had said that he crossed the pasture. Of his own accord? No, she spoke of it first. Had Mr. Hartsook offered any explanations? No, he hadn't. Had he ever paid her any attention afterward? No. Ralph declined to cross-question Hannah. To him she never seemed so fair as when telling the truth so sublimely.

Bronson now informed the court that this little trick of having the old soldier happen in, in the flick of time, wouldn't save the prisoner at the bar from the just punishment which an outraged law visited upon such crimes as his. He regretted that his duty as a public prosecutor caused it to fall to his lot to marshal the evidence that was to blight the prospects and blast the character, and annihilate forever, so able and promising a young man, but that the law knew no difference between the educated and the uneducated, and that for his part he thought Hartsook a most dangerous foe to the peace of society. The evidence already given fastened suspicion upon him. The prisoner had not yet been able to break its force at all. The prisoner had not even dared to try to explain to a young lady the reason for his being out at night. He would now conclude by giving the last touch to the dark evidence that would sink the once fair name of Ralph Hartsook in a hundred fathoms of infamy. He would ask that Henry Banta be called.

Hank came forward sheepishly, and was sworn. Lived about a hundred yards from the house that was robbed. He seen ole man Pearson and the master and one other feller that he didn't know come away from there together about one o'clock. He heerd the horses kickin', and went out to the stable to see about them. He seed two men come out of Schroeder's back door and meet one man standing at the gate. When they got closter he knowed Pearson by his wooden leg and the master by his hat. On cross-examination he was a little confused when asked why he hadn't told of it before, but said that he was afraid to say much, bekase the folks was a-talkin' about hanging the master, and he didn't want no lynchin'.

The prosecution here rested, Bronson maintaining that there was enough evidence to justify Ralph's committal to await trial. But the court thought that as the defendant had no counsel and offered no rebutting testimony, it would be only fair to hear what the prisoner had to say in his own defense.

All this while poor Ralph was looking about the room for Bud. Bud's actions had of late been strangely contradictory. But had he turned coward and deserted his friend? Why else did he avoid the session of the court? After asking himself such questions as these, Ralph would wonder at his own folly. What could Bud do if he were there? There was no human power that could prevent the victim of so vile a conspiracy as this, lodging in that worst of state prisons at Jeffersonville, a place too bad for criminals. But when there is no human power to help, how naturally does the human mind look for some divine intervention on the side of Right! And Ralph's faith in Providence looked in the direction of Bud. But since no Bud came, he shut down the valves and rose to his feet, proudly, defiantly, fiercely calm.

"It's of no use for me to say anything. Peter Jones has sworn to a deliberate falsehood, and he knows it. He has made his wife perjure her poor soul that she dare not call her own." Here Pete's fists clenched, but Ralph in his present humor did not care for mobs. The spirit of the bulldog had complete possession of him. "It is of no use for me to tell you that Henry Banta has sworn to a lie, partly to revenge himself on me for punishments I have given him, and partly, perhaps, for money. The real thieves are in this courtroom. I could put my finger on them."

"To be sure," responded the old basket-maker. Ralph looked at Pete Jones, then at Small. The fiercely calm look attracted the attention of the people. He knew that this look would probably cost him his life before the next morning. But he did not care for life. "The testimony of Miss Hannah Thomson is every word true, I believe that of Mr. Pearson to be true. The rest is false. But I cannot prove it. I know the men I have to deal with. I shall not escape with State prison. They will not spare my life. But the people of Clifty will one day find out who are the thieves." Ralph then proceeded to tell how he had left Pete Jones's, Mr. Jones's bed being uncomfortable; how he had walked through the pasture; how he had seen three men on horseback: how he had noticed the sorrel with the white left forefoot and white nose; how he had seen Dr. Small; how, after his return, he had heard someone enter the house, and how he had recognized the horse the next morning. "There," said Ralph desperately, leveling his finger at Pete, "there is a man who will yet see the inside of a penitentiary, I shall not live to see it, but the rest of you will." Pete quailed. Ralph's speech could not of course break the force of the testimony against him. But it had its effect, and it had effect enough to alarm Bronson, who rose and said:

"I should like to ask the prisoner at the bar one question."

"Ask me a dozen," said Hartsook, looking more like a king than a criminal.

"Well, then, Mr. Hartsook. You need not answer unless you choose; but what prompted you to take the direction you did in your walk on that evening?"

This shot brought Ralph down. To answer this question truly would attach to friendless Hannah Thomson some of the disgrace that now belonged to him.

"I decline to answer," said Ralph.

"Of course, I do not want the prisoner to criminate himself," said Bronson significantly.

During this last passage Bud had come in, but, to Ralph's disappointment he remained near the door, talking to Walter Johnson, who had come with him. The magistrates put their heads together to fix the amount of bail, and, as they differed, talked for some minutes. Small now for the first time thought best to make a move in his own proper person. He could hardly have been afraid of Ralph's acquittal. He may have been a little anxious at the manner in which he had been mentioned, and at the significant look of Ralph, and he probably meant to excite indignation enough against the schoolmaster to break the force of his speech, and secure the lynching of the prisoner, chiefly by people outside his gang. He rose and asked the court in gentlest tones to hear him. He had no personal interest in this trial, except his interest in the welfare of his old schoolmate, Mr. Hartsook. He was grieved and disappointed to find the evidence against him so damaging and he would not for the world add a feather to it, if it were not that his own name had been twice alluded to by the defendant, and by his friend, and perhaps his confederate, John Pearson. He was prepared to swear that he was not over in Flat Creek the night of the robbery later than ten o'clock, and while the statements of the two persons alluded to, whether maliciously intended or not, could not implicate him at all, he thought perhaps this lack of veracity in their statements might be of weight in determining some other points. He therefore suggested — he could only suggest, as he was not a party to the case in any way — that his student, Mr. Walter Johnson, be called to testify as to his — Dr. Small's — exact whereabouts on the night in question. They were together in his office until two, when he went to the tavern and went to bed.

Squire Hawkins, having adjusted his teeth, his wig, and his glass eye, thanked Dr. Small for a suggestion so valuable, and thought best to put John Pearson under arrest before proceeding further. Mr. Pearson was therefore arrested, and was heard to mutter something about a "passel of thieves," when the court warned him to be quiet.

Walter Johnson was then called. But before giving his testimony, I must crave the reader's patience while I go back to some things which happened nearly a week before and which will serve to make it intelligible.

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster

The Hoosier Schoolmaster