The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

The Boy Travelers - Africa

Boy Travelers-Africa

Study the chapter for one week.

Over the week:

Activity 1: Narrate the Chapter

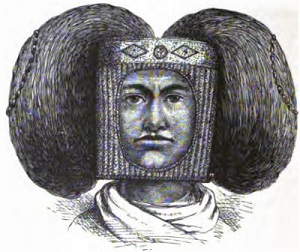

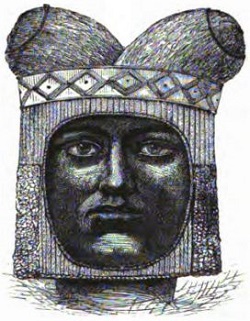

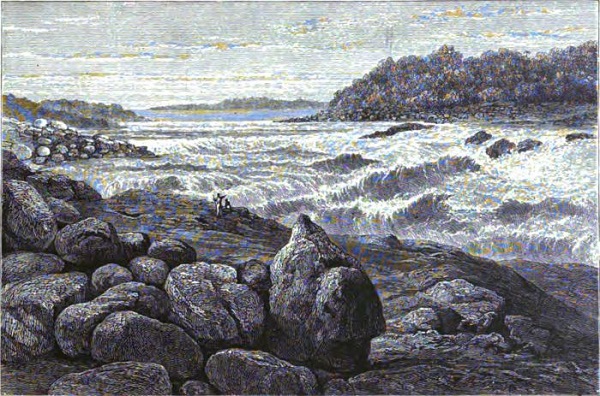

Activity 2: Study the Chapter Pictures

Activity 3: Observe the Modern Equivalent

Examine the chapter setting in modern times:

Activity 4: Map the Chapter

Study the map of Tanzania and find or answer the following:

Activity 5: Map the Chapter on a Globe